What Is Gamma in Options Trading?

Learn what gamma measures in options trading, why it matters, and how it affects your position's delta as the stock moves.

Gamma measures how much an option’s delta changes when the stock price moves $1. While delta tells you your immediate directional exposure, gamma tells you how that exposure will shift as the stock moves.

Think of delta as your speed and gamma as your acceleration. Delta shows how fast your position’s P/L changes; gamma shows how quickly that speed will change.

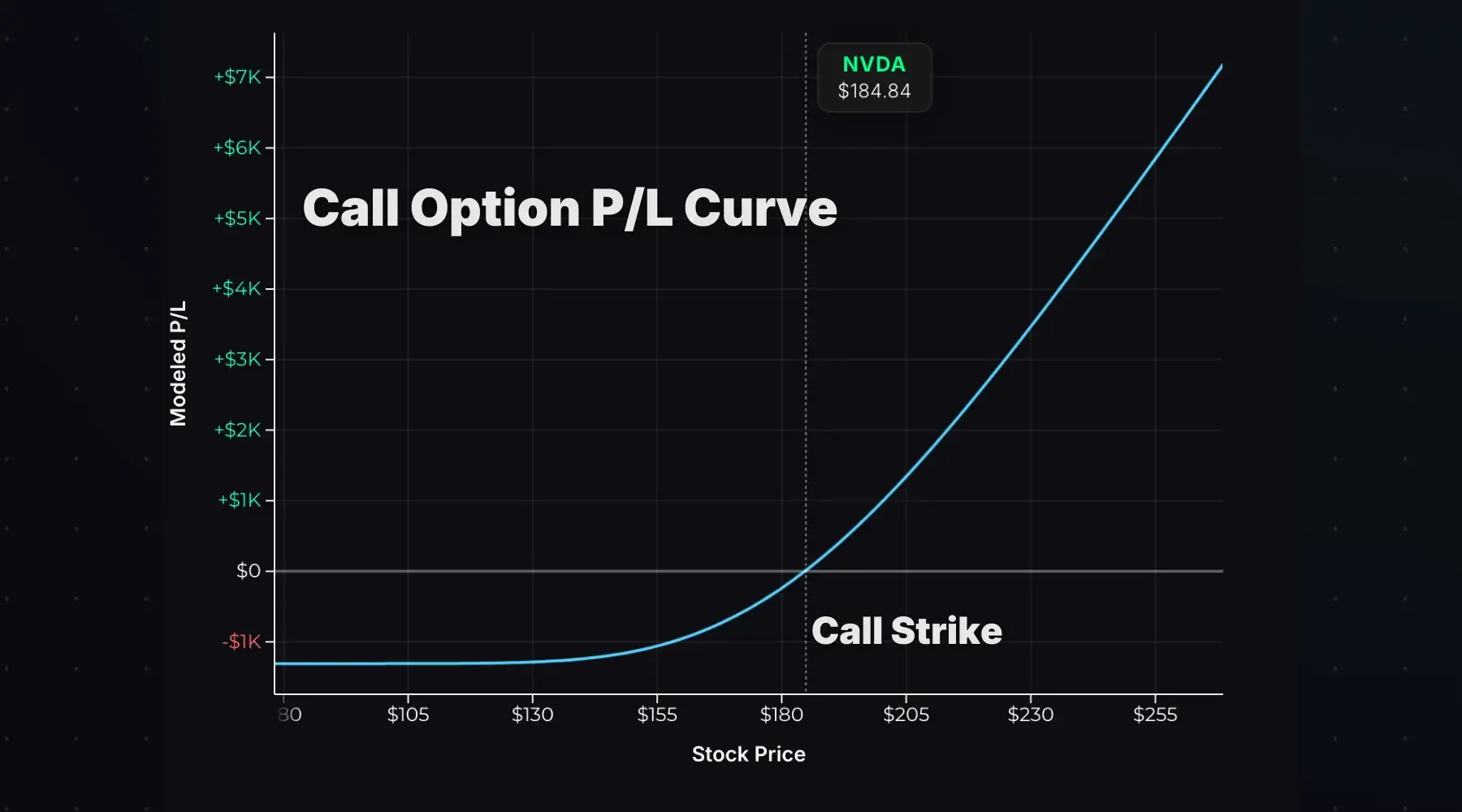

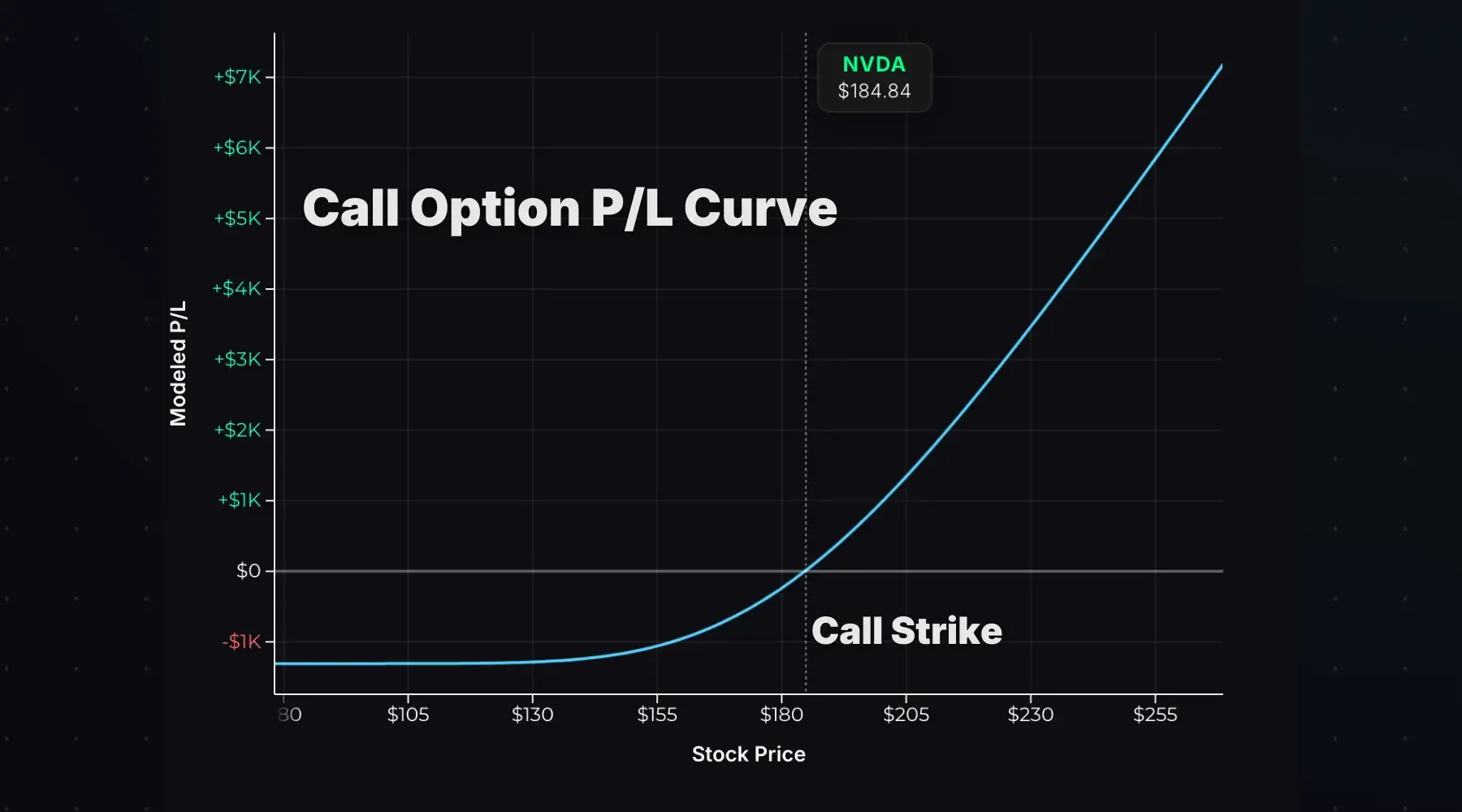

On a call option’s P/L curve, you can see gamma visually:

When the option is deep out of the money, the curve is nearly flat—delta is close to zero and barely changes. As the stock rises toward the strike and beyond it, the curve steepens. That steepening is gamma at work.

How Gamma Changes with Price and Time

Gamma and Strike Price

Gamma is highest for at-the-money options and lowest for deep in-the-money or out-of-the-money options.

Why? A deep OTM option has a delta near zero—it’s almost certainly expiring worthless. A small change in the stock price won’t notably shift that probability, so the delta remains stable at zero.

The image below shows a $100 stock and a call with a strike of $120 with 10 days to expiration. The stock has to increase over 20% for the call to have value at expiration—an extremely low probability. So for a $1 increase from $100 to $101, the 120 call’s value won’t change much. The next $1 increase doesn’t matter either with a delta of 0.01. That stable delta is zero gamma.

A deep ITM option has a delta near 1—it’s almost certainly expiring with value. The 120-strike put is $20 ITM with 10 days to expiration—it’s almost certainly going to expire ITM—its delta is -1.00. A $1 stock price change barely shifts that probability. In both cases, a $1 stock move doesn’t meaningfully change those probabilities, so delta barely budges. Low delta change means low gamma.

In both instances above, we can see the deltas pinned at the extremes with zero gamma, indicating how deep ITM and OTM option deltas are stable.

At-the-money options sit at the inflection point. A $1 move in either direction meaningfully shifts the probability of expiring in the money, especially near expiration, so delta changes substantially. High delta change means high gamma.

ITM and OTM Gamma as Expiration Approaches

The passage of time has an effect on gamma, either increasing exponentially or tapering off to zero.

For ITM and OTM options, gamma decreases as expiration approaches. The option’s fate becomes increasingly certain—it will almost definitely expire in or out of the money—so delta stabilizes near 0 or 1.

Compare the delta and gamma values of a $120-strike call option on a $100 stock with 365 DTE and 5 DTE:

The call has a chance of expiring ITM with 365 days to expiration—the stock can reasonably move $20 in a year, so its delta is non-zero and gamma is low but positive. But if the stock is still $100 with 5 days to expiration, the call has virtually no chance of expiring ITM. Its delta will be zero with zero gamma—a $1 stock price increase still means the 120 call is almost certain to expire worthless.

ATM Option Gamma as Expiration Approaches

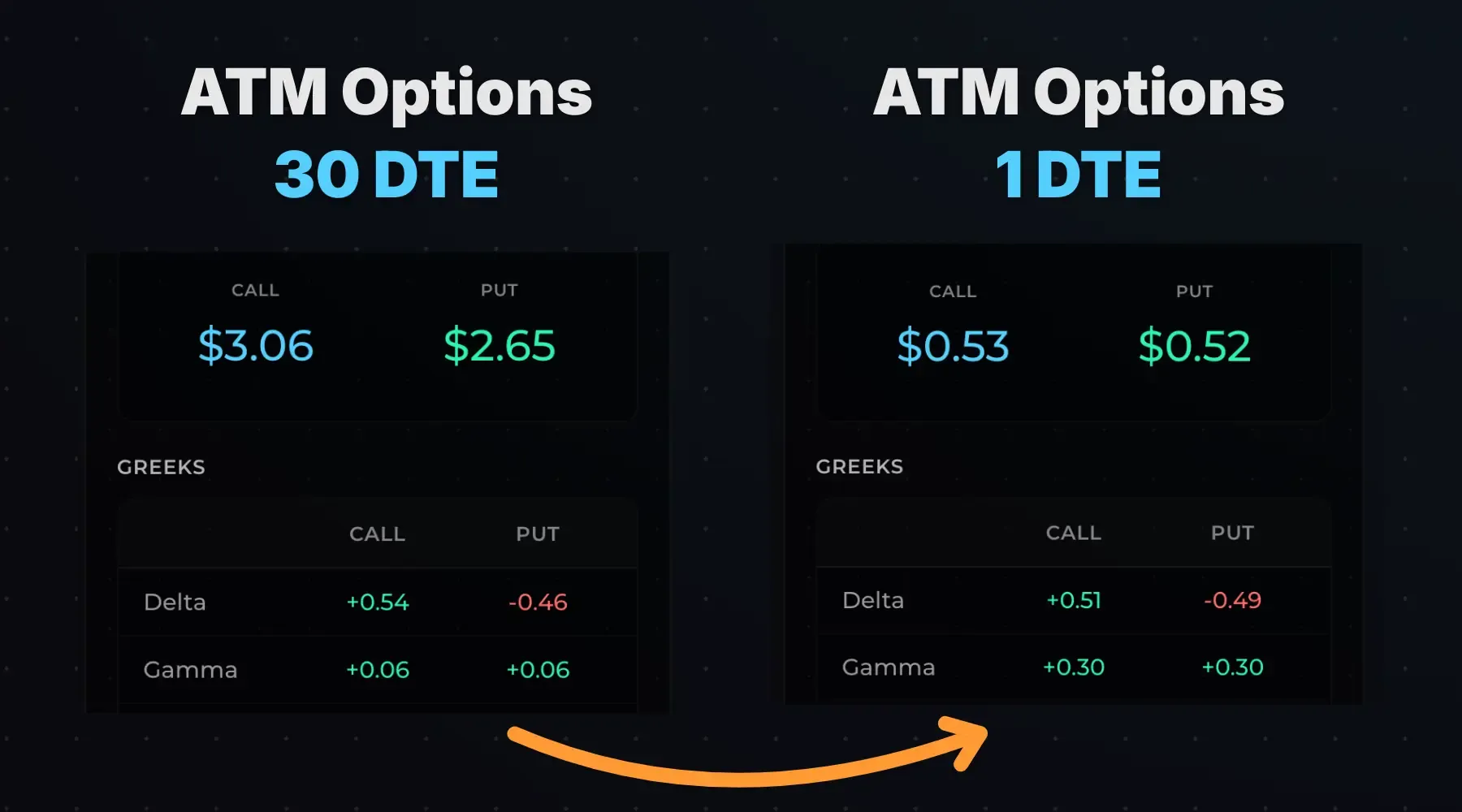

The image below shows at-the-money options with 30 DTE vs. 1 DTE. The deltas remain relatively unchanged, but the gamma levels explode:

Consider the call option above with a $100 strike when the stock is at $100. With 30 days left, the option has a +0.54 delta. If the stock drops to $99, the delta falls to +0.48 (original delta minus 0.06 gamma). There’s still plenty of time for the stock to recover.

Now imagine the same scenario with one day left. If the stock drops from $100 to $99, the 100 call’s delta moves from +0.51 to +0.21—a substantial decrease. That’s because with one day to expiration and the stock now $1 below the call strike, the probability of the call expiring ITM falls dramatically. The lower delta represents the option trading less like stock since it has a much lower probability of becoming stock.

This is why ATM options near expiration have the highest gamma—small price changes cause dramatic swings in delta, driven by the dramatic shift in the option’s probability of expiring ITM.

Hover over the interactive chart below to compare the modeled gamma values for a call option with a strike price of $150 at various amounts of time to expiration:

Gamma and Delta: How They Work Together

Delta tells you your current directional exposure; gamma tells you how that exposure evolves.

For example: a call option has a delta of 0.50 and gamma of 0.05. If the stock rises $1, the new delta becomes 0.55. If it rises another $1, delta becomes 0.60.

A position with high gamma will see its delta—and therefore its risk profile—shift quickly. A position with low gamma will behave more predictably. This is why high gamma positions are difficult for delta hedgers—small stock moves require constant delta adjustments.

Long Gamma vs Short Gamma

Every options position is either long gamma (positive gamma) or short gamma (negative gamma). This distinction fundamentally shapes how your position responds to price movement.

What Is Long Gamma?

Outright option purchases have long gamma. This includes long calls, long puts, long straddles, and long strangles.

Long gamma means your delta moves in your favor as the stock moves. When you’re right, you get more right. When you’re wrong, you get less wrong.

For a long call: as the stock price rises, delta increases from 0.50 toward 1.00. Each additional $1 of upside contributes more to your profit. If the stock falls instead, delta decreases toward zero. Each additional $1 of downside hurts less than the one before:

This creates the characteristic curved P/L of long options—accelerating gains, decelerating losses.

What Is Short Gamma?

Net options-selling strategies have short gamma. This includes short calls, short puts, short straddles, iron condors, and iron butterflies (when the stock is in between the short strikes).

Short gamma means your delta moves against you as the stock moves. When you’re wrong, you get more wrong.

Consider this short 665 straddle on META:

The cyan line (T+0) is the modeled P/L curve at entry. The initial position delta is -6.38 with a gamma of -1.05. This means the delta will become more negative as the stock price rises and more positive as the stock price falls. We can see how the position P/L drops as the stock falls, and the T+0 curve slopes up and to the right—that’s positive delta.

If the stock drops to $600 right after entry, the short 665 straddle has a delta of +59. So as the stock price is falling and the short straddle is losing money, the delta becomes more positive, which means subsequent stock price drops hurt even more. This is the danger of being short gamma.

Note: complex or multi-leg option positions can be negative gamma in one zone and positive gamma in others (and vice versa). A short iron condor is short gamma when the stock price is between the short strikes, but becomes positive gamma when the stock is beyond either long strike.

Managing Gamma Risk

Gamma itself isn’t inherently dangerous—context matters.

If you own options, high gamma is often beneficial. When a long call’s delta increases from 0.50 to 0.80 as the stock rallies, that’s gamma working for you. Your gains accelerate. And since long options have defined risk, the downside is capped regardless of gamma.

Gamma becomes a genuine risk when you’re short options. A short call sold at 0.30 delta can see that delta grow to 1.00 as the stock rallies. Each incremental move against you hurts more than the last, and losses can compound quickly.

When Gamma Works Against You

The danger zone is short options near expiration. This is where gamma peaks for ATM options, meaning your delta—and your risk—can swing violently with small price moves. A stock moving $2 against you on expiration day can be far more damaging than the same move three weeks earlier.

How to Manage It

Avoid selling short-dated options. The closer to expiration, the more gamma exposure you face. Selling options is particularly risky short-term because the losses are significant and profits are capped. High gamma benefits short-term option buyers playing for big price swings—their positions explode in value when they’re right.

Trade spreads instead of naked options. A bear call spread still has negative gamma, but the long call partially offsets the negative delta and gamma of the short call. Most importantly, a bear call spread has limited loss potential, so the losses can’t compound to an unmanageable level assuming appropriate position size.

Respect position size. If you’re running short gamma strategies, especially short straddles and strangles, size positions so that even the worst-case delta swings don’t threaten your account. The accelerating losses of negative gamma demand conservative sizing.

Next: What Is Theta? — Learn how time decay erodes option prices.

Related Resources

- What Is Delta in Options Trading? — Directional risk explained

- What Is Vega in Options Trading? — IV sensitivity explained

- Options Greeks Overview — Learn about all four primary Greeks

- Options Pricing Calculator — Calculate gamma and other Greeks