What Is a Covered Call?

How covered calls work, when to sell them, and how to calculate max profit, breakeven, and risk.

A covered call is a neutral to slightly bullish options strategy where you own 100 shares of stock and sell a call option against those shares. You’re “covered” because you already own the shares you might have to deliver if assigned on the call. In exchange for capping your upside, you collect a premium that provides income and lowers your risk.

The covered call options strategy is popular among shareholders who want to generate income while waiting to sell their shares at a higher price. The strategy works well in sideways or moderately bullish markets where the stock isn’t expected to make a dramatic move higher.

How Covered Calls Work

To set up a covered call, you need two things: 100 shares of stock (for each call you sell) and a short call option at a strike price above the current share price.

When you sell the call, you collect a premium. This premium is yours to keep no matter what happens, as long as you hold the covered call to expiration.

In exchange, you’re obligated to sell your shares at the call’s strike price if the stock is above it at expiration. If the stock finishes below the strike, the call expires worthless, you keep your shares, and you keep the full premium from selling the call.

Hover over the chart below to analyze the payoff potential of a covered call. The chart compares holding a $150 stock vs. selling a 160 call against the shares for $5.00 in premium.

Let’s walk through some examples.

Covered Call Example

You own 100 shares of a $185 stock and sell a call with a strike price of $200 for $10 with 45 days to expiration (DTE).

In plain English: you own stock at $185 and are selling an option that caps your upside on the shares at any price above $200. For this sacrifice, you collect a premium, which you can think of as a reward for capping your upside.

Selling a call for $10 generates $1,000 in premium collection ($10 call price × 100 shares). Here are the key metrics for this covered call position:

Note: The cash requirement is the amount required to enter this position from scratch (buy the stock and sell the call). In our example we’re assuming the stock was already held and the trader sold the call against it.

Let’s explore some potential outcomes for this trade:

Shares rise to $230: Your shares get called away at $200. You profit $15 per share on the stock plus $10 per share in premium = $2,500 total.

This is the “Shares Called Away” profit scenario, where the maximum profit is achieved. A standalone stock position makes $4,500 while the covered call makes $2,500, but both strategies profit:

Stock rises to the call strike: The call expires worthless. You keep your shares and the $1,000 premium. You profit on both parts of the trade. You make $1,500 on the shares and $1,000 on the call option for a total profit of $2,500:

You outperform a standalone stock position by $1,000 (the premium received for selling the call). This is the best-case scenario since you can then sell another call in a future expiration at a higher strike price.

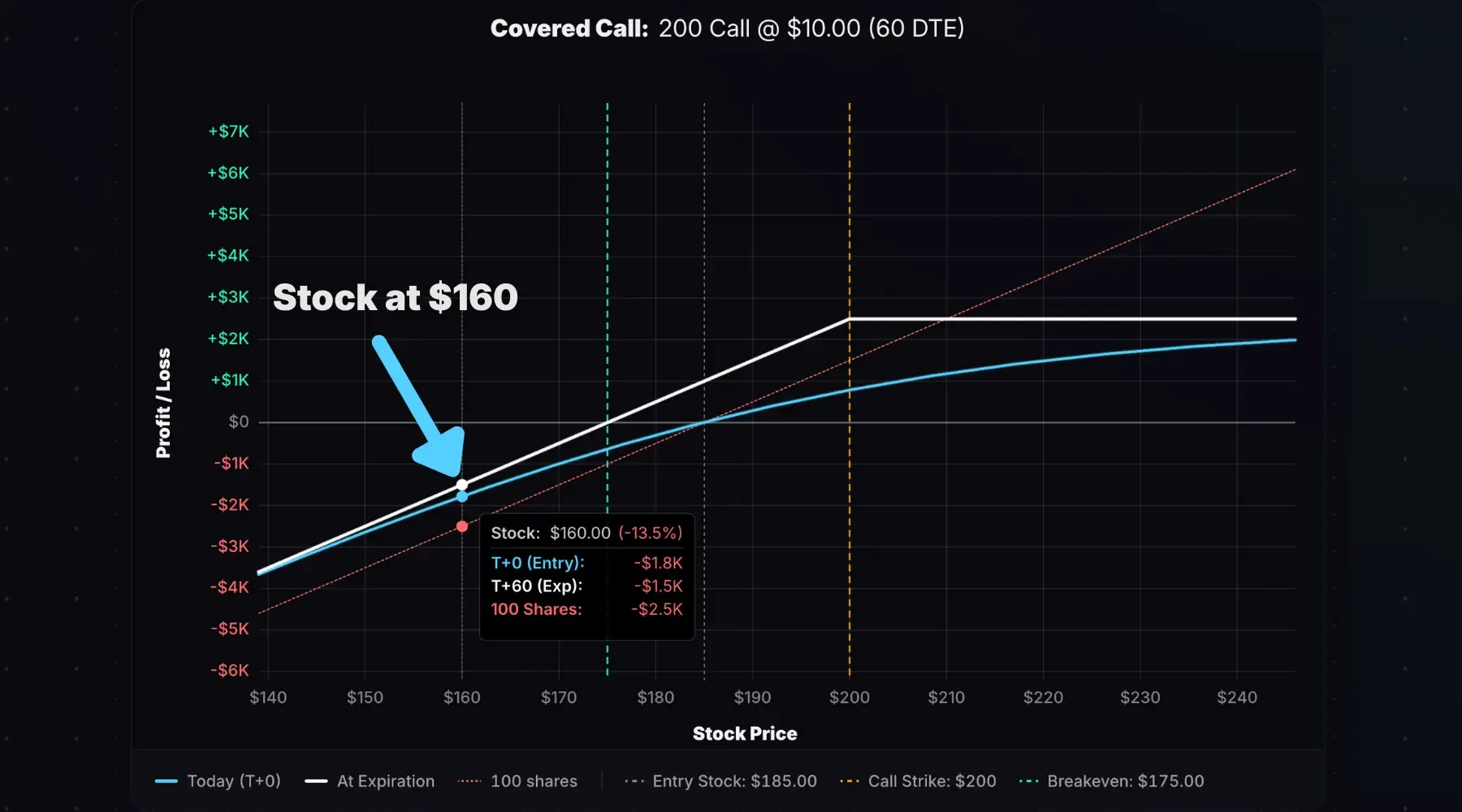

Stock falls to $160: You lose $2,500 on the shares but make $1,000 on the call option you sold. Your net P/L is -$1,500:

Notice how the standalone stock position loses more money than the covered call at every point on the downside. This is the cushion provided by the call premium collected when selling the call. For this reason, covered calls are always safer than holding standalone stock positions, which is why the covered call strategy is a great starting point for stock investors looking to incorporate options into their portfolios.

Covered Call Payoff Diagram

We’ve already looked at many payoff diagrams, but I want to explain further how to read and interpret the charts.

Let’s look at an interactive covered call payoff diagram:

Position Components: Buy 100 shares of stock at $200 and sell a 220 call with 60 days to expiration for $9.20 (collect $920)

The Entry (60 DTE) line shows the expected P/L of the position at entry. So if the stock makes a big move on day one, the cyan line shows the expected outcome.

The Expiration line shows the P/L at expiration in 60 days.

The dashed purple line (Stock Only) shows the P/L of a standalone stock position purchased at $200. No call sold.

Hover over the chart at $200, where the Entry stock price reference line is. You’ll see the Entry P/L is around $0 since the position was just entered. Now hover to higher stock prices. You’ll see the covered call P/L increase, but not as much as it will be at expiration. That’s because the call you sold has time value in it. As time passes with the stock below the strike of $220, the call will lose value steadily, and you’ll see increasing profits on that portion of the trade.

That’s why at $220, the Entry P/L line shows a profit of about $1,000 while the Expiration P/L shows +$2,900. If the stock makes a quick move higher, you’ll have profits on the stock position but losses on your short call. As time passes, the call will lose its extrinsic value, leaving only intrinsic value at expiration.

Call Option Decay Curve

Here’s a visual of this hypothetical 220 call option’s decay with the share price at $220, assuming the call has 60 days to expiration and implied volatility is 50%:

Learn more about theta decay.

With 60 DTE, the theoretical call price is over $18.00 ($1,800+ premium). If we initially sold the call for ~$900 when the stock price was $200 and the stock rose to $220 quickly, and the call is now $1,800, we have an unrealized loss of $900 on the call portion of the covered call.

The curve above shows how the call option will decay over time if the share price stayed pinned at $220. We can see the call steadily loses value over time and is worthless at expiration.

That’s why the Entry P/L line is much lower than the Expiration P/L line for a covered call when the shares rise to the short call strike on the first day.

Maximum Profit and Maximum Loss

Let’s learn how to calculate the maximum profit and maximum loss for a covered call position.

Maximum Profit = (Strike Price − Stock Purchase Price + Premium) × 100

In our first example: ($200 call strike − $185 stock purchase price + $10 premium) × 100 = $2,500

The maximum profit occurs when the stock closes at or above the call strike at expiration. Your shares are called away, but you’ve captured the full move up to the strike, and kept the premium from the call.

Maximum Loss = (Stock Purchase Price − Premium) × 100

In our example: ($185 − $10) × 100 = $17,500

The maximum loss occurs if the stock goes to zero. You lose the full value of your shares minus the premium received. This is similar to the risk of owning stock, just slightly cushioned by the call premium.

Breakeven Price

The expiration breakeven for a covered call is: Stock Cost Basis − Premium Received

In our example: $185 − $10 = $175

If the stock is exactly $175 at expiration, you make $10 profit per share from the call premium, but you lose $10 per share on the stock.

Covered Call vs Holding Stock

How does a covered call compare to simply holding shares?

Let’s compare with another interactive payoff chart:

At any price below the strike, the covered call outperforms a standalone stock position. You have the same stock exposure, but the premium provides a cushion that reduces losses on the overall position. At $90, the stock is down $1,000, but the covered call is only down $540.

At prices well above the strike, the stock outperforms. If the stock rallies to $125, the stock gains $2,500, but the covered call is capped at $1,460. You’ve given up $1,040 of upside.

When to Sell Covered Calls

Covered calls work best in specific market conditions:

You’re neutral to slightly bullish: You think the stock will stay flat or rise modestly, but not rocket higher. The golden scenario is the stock drifting up to your strike price at expiration.

You’re willing to sell the stock at the strike: If you’ve had a profitable stock position that you’d be happy to sell at a higher price, the covered call provides a natural exit strategy. If you absolutely do not want to sell the shares, selling covered calls isn’t suitable.

High IV environments: When implied volatility is elevated, you collect richer premiums for the same call strike.

The stock just rallied and you think a reversal might happen: If the stock just ripped higher and you’re expecting near-term downside price action, but don’t want to sell your shares, then selling an OTM call can cushion downside exposure slightly while still allowing for more profit potential if the shares keep rising.

Strong upside price movements often coincide with increases in IV, so you might be able to lock in a juicy premium for selling a far OTM call against your shares, giving you lots of room to continue profiting if the rally continues, or a nice premium collection and downside risk cushion if the stock reverses.

Strike Price Selection

How do you choose a strike price for a covered call? Let’s look at an example from our covered call calculator to compare two different strikes on the same stock:

The 210 call is closer to the share price of $200. It collects more credit, has a lower breakeven (more downside risk protection), but lower maximum profit potential since it caps gains on the stock at $210 compared to $220 on the higher strike call.

The 220 call is further from the share price. It collects less credit, has a higher breakeven (less downside risk protection), but higher maximum profit potential since it gives the stock more room to run before hitting the capped profit zone (above the call strike).

Here are the key considerations when choosing which strike to sell:

Selling ATM or near-ATM calls (strike is close to the stock price):

- Higher premium collected

- Lower breakeven (more downside protection)

- Higher probability of getting shares called away

- Less room for the stock to appreciate

- Overall: more neutral.

OTM strikes (above current price):

- Lower premium collected

- Higher breakeven (less downside protection)

- Lower probability of getting shares called away

- More room for stock price appreciation before profit cap kicks in

- Overall: more bullish.

If you’re selling call options on stock you want to keep, choose a higher strike to reduce assignment risk. If you’re comfortable selling sooner and at a lower price, selling calls closer to ATM will accomplish that.

Choosing an Expiration Date

Covered call traders will typically target 30 to 60 days to expiration on the calls they sell. This window strikes a balance between:

- Selling short-term options with strike prices very close to the underlying stock price

- Selling long-term options and locking yourself into one strike price for a long period of time.

Selling short-term calls, such as weekly call options, requires you to sell strikes very close to the stock price to collect any meaningful credit.

Selling long-term call options, such as 6-12 months to expiration, allows you to sell further out-of-the-money strikes for hefty premiums, but locks you into one strike for the duration of the trade.

Managing a Covered Call

You don’t have to hold a covered call to expiration. Active management can improve returns, and sometimes makes more logical sense than holding to expiration.

Here are some covered call management strategies to consider:

Close early at 50-75% of max profit: If the call option has decayed significantly but expiration is still weeks away, consider buying it back for a profit. This lets you sell another call option sooner, potentially generating more income than waiting. The logic: with 75% of profit captured, you’re still capping your upside profit potential with little left to gain from holding the call.

Rolling up and out: If the stock rises toward your strike before expiration, you can “roll” the short call position—buy back the short call and sell a new one at a higher strike and/or further expiration. If you roll out in time (buy back your short call and sell a new one at the same strike but further expiration), you’ll collect more premium but stay locked into the same short strike. If you roll up and out, you’ll be selling a higher strike price (up) in a further expiration (out). You won’t collect as much credit as rolling out to the same strike, but you’ll give the covered call more upside. This is a good strategy to use when you expect the stock price to continue running after moving towards your original short call strike.

Letting it expire vs closing: If the call is far OTM near expiration, you can let it expire worthless to avoid paying commissions. But if it’s close to the stock price, consider closing to avoid the uncertainty of getting assigned on a last-minute stock price movement that leaves your call ITM.

Risks of Selling Covered Calls

Full downside stock exposure: The foundation of a covered call is owning stock, which loses money increasingly as the stock price falls. The premium from selling a call cushions this loss, but only slightly.

Capped upside: The biggest risk isn’t an explicit loss—it’s opportunity cost. If your stock doubles, you’re stuck with a limited profit when just holding the stock on its own would have made way more money. You still profit, but it might sting to see your original long stock position with significantly more profits than the covered call.

Triggering taxable events: Getting shares called away means selling your stock, which means realizing gains. It also means you no longer own the shares—if you want back in, you’ll need to buy at the current price and restart the clock on getting into long-term capital gains on the long stock position.

Covered Call Assignment

What happens if you get assigned on a covered call?

The short call expires ITM: If the stock is above the call strike at expiration, your broker will automatically sell your 100 shares at the strike price. The premium you collected is already in your account. You realize max profit but your position is exited.

Early assignment: American-style options can be assigned before expiration. Early assignment on a short call typically happens when the call is deep ITM with little extrinsic value, or before an ex-dividend date and the ITM call’s extrinsic value is less than the dividend. If assigned early, you simply sell your shares sooner than expected. You still achieve the maximum profit, just sooner than expiration.

The Bottom Line

The covered call options strategy lets you generate income from stock you already own by selling the right to your shares at a specific price. You get paid while waiting to sell your shares at a higher price. The trade-off is simple: you lose the unlimited upside on your stock, so covered calls aren’t ideal if you’re extremely bullish on the stock.

In essence, the covered call is an options strategy where you sell the upside on your stock. If the stock doesn’t rise above your strike, you can keep selling calls indefinitely and generate income from your stock position, like creating your own dividend stream.

Covered calls pair naturally with cash-secured puts in the wheel strategy—a repeating cycle that uses both strategies.

Use our covered call calculator to model your covered call trades and visualize potential outcomes.